Founded in August 1919 in New York City by Louis Marx and his brother David, the company’s basic aim was to “give the customer more toy for less money,” and stressed that “quality is not negotiable” – two values that made the company highly successful. Initially, after working for Ferdinand Strauss, Marx, born in 1894, was a distributor with no manufacturing capacity. All product production would have to be contracted out for the first few years. Marx raised money as a middle man, studying available products, finding ways to make them cheaper, and then closing sales. Enough funding was raised to purchase tooling from previous employer Strauss for two obsolete tin toys – the Alabama Coon Jigger and Zippo the Climbing Monkey. With subtle changes, Marx was able to turn these toys into hits, selling more than eight million of each within two years. Another success was the “Mouse Orchestra” with tinplate mice on piano, fiddle, snare, and one conducting.

Founded in August 1919 in New York City by Louis Marx and his brother David, the company’s basic aim was to “give the customer more toy for less money,” and stressed that “quality is not negotiable” – two values that made the company highly successful. Initially, after working for Ferdinand Strauss, Marx, born in 1894, was a distributor with no manufacturing capacity. All product production would have to be contracted out for the first few years. Marx raised money as a middle man, studying available products, finding ways to make them cheaper, and then closing sales. Enough funding was raised to purchase tooling from previous employer Strauss for two obsolete tin toys – the Alabama Coon Jigger and Zippo the Climbing Monkey. With subtle changes, Marx was able to turn these toys into hits, selling more than eight million of each within two years. Another success was the “Mouse Orchestra” with tinplate mice on piano, fiddle, snare, and one conducting.

Marx listed six qualities he believed were needed for a successful toy: familiarity, surprise, skill, play value, comprehensibility and sturdiness. By 1922, both Louis and David Marx were millionaires. Initially, Marx reevaluated and produced a few original toys by predicting the hits and manufacturing them less expensively than the competition. The yo-yo is an example: although Marx is sometimes wrongly credited with inventing the toy, the company was quick to market its own version. During the 1920s, about 100 million Marx yo-yos were sold.

Unlike most companies, Marx’s revenues grew during the Great Depression, with the establishment of production facilities in economically hard-hit industrial areas of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and England. By 1937, the company had more than $3.2 million in assets ($42.6 million in 2005 dollars), with debt of just over $500,000. He was declared “Toy King of the World” in October 1937 in a London newspaper. By 1938, Marx employed 500 workers in the Dudley factory and 4000 in the American factories.[9] Marx was the largest toy manufacturer in the world by the 1950s. Fortune Magazine in January 1946 had declared him “Toy King” suggesting at least $20 million in sales for 1941, but again in 1955, a Time Magazine article also proclaimed Louis Marx “the Toy King,” and that year, the company had about $50 million in sales. Marx was the star article of the magazine with his picture displayed on the front cover. Marx was the initial inductee in the Toy Industry Hall of Fame, and his plaque proclaimed him “The Henry Ford of the toy industry.”

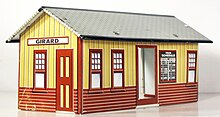

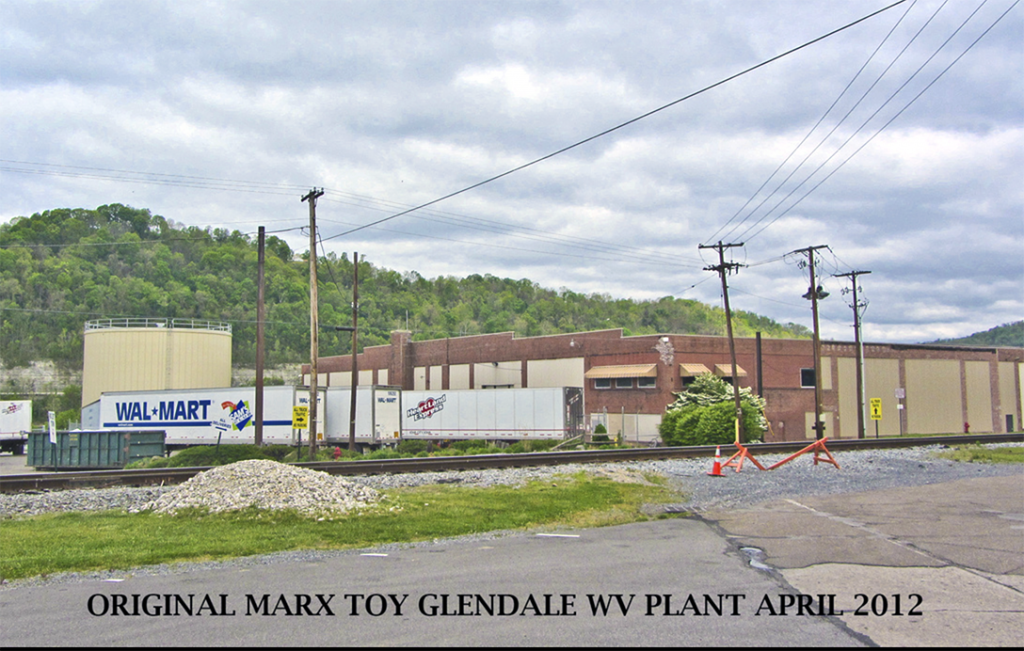

At its peak, Louis Marx and Company operated three manufacturing plants in the United States: Erie, Pennsylvania, Girard, Pennsylvania, and Glen Dale, West Virginia. The Erie plant was the oldest and largest, while the Girard plant, acquired in 1934 with the purchase of Girard Model Works, produced toy trains, and the Glen Dale plant produced toy vehicles. Additionally, Marx operated numerous plants overseas, and in 1955 five percent of the toys Marx sold in the US were made in Japan. In 1952 Marx Company stationary listed operations in: Mexico, London England, Swansea Wales, Durbin South Africa, Sydney Australia, Toronto Canada, Sao Paulo Brazil and Paris France. By 1959, the demand for American toys was a billion dollars a year.

Marx enjoyed his wealth at his 20.5-acre estate in the wealthy suburb of Scarsdale, north of New York City. The estate featured a 25-room Georgian mansion, a barn and stables for horses he raised and other amenities. The estate was sold to a developer after his death in 1982, to make way for some 29 homes.

Playsets

Among the most enduring Marx creations were a long series of boxed “playsets” throughout the 1950s and 1960s based on television shows and historical events. These include “Roy Rogers Rodeo Ranch” and Western Town, “Walt Disney’s Davy Crockett at the Alamo”, “Gunsmoke”, “Wagon Train”, “The Rifleman Ranch”, “The Lone Ranger Ranch”, “Battle of the Blue and Grey”, “The Revolutionary War” (including “Johnny Tremain”), “Tales of Wells Fargo”, “The Untouchables“, “Robin Hood”, “The Battle of the Little Big Horn”, “Arctic Explorer”, “Ben Hur”, “Fort Apache”, “Zorro”, “Battleground”, “Tom Corbett Training Academy”, and many others. Playsets included highly detailed plastic figures and accessories, many with some of the toy world’s finest tin lithography. A Marx playset box was invariably bursting with contents, yet very few were ever priced above the average of $4–$7. Greatly expanded sets, such as “Giant Ben Hur” sold for $10 to $12 in the early 1960s. This pricing formula adhered to the Marx policy of “more for less” and made the entire series attainable to most customers for many years. Original sets are highly prized by baby boomer collectors to this day. Collector’s books titled “Boy Toys” and “The Big Toy Box at Sears” feature the original advertisements for many of these sets and are well worth having as a visual reference.

Marx produced dollhouses from the 1920s into the 1970s. In the late 1940s Marx began to produce metal lithographed dollhouses with plastic furniture (at the same time it began producing service stations). These dollhouse were variations of the Colonial style. An instant sensation was the “Disney” house, featured in the 1949 Sears catalogue. The popularity of Marx dollhouses gained momentum, and up to 150,000 Marx dollhouses were produced in the 1950s. Two house sizes were available, with two different size furniture to match; the most popular in the 1/2″ to 1′ scale, and the larger 3/4″ to 1′ scale. An L-shaped ranch hit the market in 1953, followed by a split-level of 1958. Curiously, in the early 1960s a dollhouse with a bomb shelter was sold briefly.

As the space race heated up, Marx playsets reflected the obsession with all things extraterrestrial such as “Rex Mars”, “Moon Base”, “Cape Canaveral”, and “IGY International Geophysical Year”, among other space themed sets. In a similar theme, Marx also capitalized on the robot craze, producing the Big Loo, “Your friend from the Moon”, and the popular Rock’em Sock’em Robots action game.

In 1963, Marx began making a series of beatnik style plastic figurines called the Nutty Mads, which included some almost psychedelic creations, such as Donald the Demon — a half-duck, half-madman driving a miniature car. These were similar to the counterculture characters of other companies introduced about a year before, such as Revell’s Rat Fink by “Big Daddy” Ed Roth, or Hawk Models’ “Weird-Oh’s“, designed by Bill Campbell.

Louis Marx and Company entered a five-year selling contract with Girard Model Works in 1929 and in 1932 contracted Woods/Girard to exclusively produce all his trains and toys. The trains were called Joy Line.[14] These were small four inch tinplate cars with a small windup or electric engine. Marx officially acquired the company in 1935, although his brand appears on floor trains, trolleys, Joy Line and the M10000 sets, years before the acquisition. This was the beginning of Marx trains. In 1934 Marx produced its first newly designed model train set, the streamlined Union Pacific M-10000.[15][page needed] The streamlined Marx Commodore Vanderbilt was issued in 1935 with new 6 inch tinplate cars. The ever popular Marx Canadian Pacific 3000 appeared in 1936 in Canada, while the articulated Marx Mercury was introduced to America. The success of Marx “027” train line forced other manufacturers to follow suit in size and fashion. Marx continued to make tinplate train sets until 1972. Plastic sets began in 1952 and only plastic sets were made after 1973, until the end of the company in 1975.

Toy King Overtakes Lionel

Even though Marx trains never held the prestige of Lionel’s trains, they were able to outsell them for most of the late fifties. While Lionel’s top mid-fifties toy sales were some $32 million, the Marx’s 1955 toy sales were $50 million.[4] When it comes to quality and quantity, Louis Marx and Company is considered “the most important producer of inexpensive American toy trains”.

Vehicles

Pre-war

Cast iron was unwieldy, heavy, and not well-suited to proper detail or model proportions and gradually it was replaced by pressed tin. Marx offered a variety of tin vehicles, from carts to dirigibles — the company would lithograph toy patterns on large sheets of tinplated steel. These would then be stamped, die-cut, folded, and assembled. Marx was long known for its car and truck toys, and the company would take small steps to renew the popularity of an old product. In the 1920s, an old truck toy that was falling behind in sales was loaded with plastic ice cubes and the company had a new hit. The Honeymoon Express, a wind-up train on track with a plane circling above, later became the Mickey Mouse Express and then the Subway Express. Popeye pushing a barrel of spinach eventually became the 1940 Tidy Tim Street Cleaner and Charlie McCarthy in his “Benzine Buggy”.

Some of the most popular vehicles were Crazy Cars like the Funny Flivver of 1926 — another was the eloping “Joy Riders”. One earlier and much sought after tin toy was an open Amos ‘n Andy Ford Model T four door, as well as another Model T with driver apparently on a European jaunt and hauling a trunk at the rear with the names of various European cities on it. This model was produced in a variety of liveries. Lithographed tin tanks, airplanes, police motorcycles, tractors, trains, luxury liners, and rocket ships were all produced in bright colors. One toy, the Tricky Taxi seems to have had origins in a Heinrich Muller toy from Nuremberg in Germany. The 1935 G-Man pursuit car was possibly the largest vehicle Marx ever made at 14½ inches long. Even doll houses, gasoline stations, parking lots and street scenes were made in tin. That Marx was doing well even in the depression is shown by the date of introduction of their well-known motorcycle cop toy — 1933.

A number of tinplate trucks, buses and vans were made in the 1930s, particularly in the latter part of the decade. Trucks were made, particularly Studebakers, in a variety of colors and formats, and often advertised in Sears catalogues. These included several different series like the truck hauling five tinplate “stake bed” trailers, a “dumping” garbage truck, many variations on larger truck “car carriers” hauling different vehicles, and a set of completely chromed trucks. Metal gas and fire station sets could also be purchased on which to play with the vehicles more fully.

Lumar toys

“Lumar Lines” was another name used for a line of floor operated tin toys, trucks, vehicles, trains beginning in the early 1930s, in the United States and England. Lumar Lines passenger and freight floor trains were produced from 1939 through 1941. Production continued after WWII with the “Friendship” train that honored the real train that had sent supplies from the United States to England in 1947. The “standard gauge” floor train was first marketed in 1933 under the “Girard Model Works” moniker.

Plastics

Louis Marx and Company was an early player in the plastic toy field. After World War II Marx introduced more vehicles, taking advantage of molding techniques with various plastics. Pressed tin and steel remained in the form of Buicks, Nashes, or other semi-futuristic sedans, race cars, and trucks that didn’t replicate any actual vehicles. One car was a tin Buick-like wood-bodied station wagon. These were often of various larger sizes, ranging from 10 to 20 inches long. Some vehicles were difficult to identify as Marx; one had to look for the small “X-in-O” logo, usually on the lower rear of the vehicle. Often there were no markings on the base.

More and more, however, plastic models appeared in a variety of sizes, three series of which are significant. The first series, in 1950, included inexpensive 4-inch replicas of early 1950s cars, both foreign and domestic, like Talbot, Volkswagen, Jaguar, Studebaker, Ford, Chevrolet, GMC Van and others. They were supplied as accessories for Marx’ large tinplate gas station or rail station toys. These were molded of polystyrene and came with die-cast metal wheel-and-axle combinations. The second series was identical, except for updating the cars to 1954 models. The third series, released in 1959, included updated models of 1959 cars, only these were molded in polyethylene and had polyethylene wheels/axles, and were supplied with an updated 1959 gas station. The Marx 1959 gas station cars were downsized and simplified versions of AMT and Jo-Han flywheel models.

In the early 1950s, one Marx product line showed a greater sophistication in toy offerings. The “Fix All” series was introduced, whose main attraction was larger plastic vehicles (about 14 inches long) that could be taken apart and put back together with included tools and equipment. A 1953 Pontiac convertible (erroneously identified on packaging as a sedan), and a 1953 Mercury Monterey station wagon which featured an articulated drive-line. Everything from the pistons to the crankshaft to the rear axle gears were visible through clear plastic, and wood-trim decals for the sides finished off this marvelous model. A very large 1953 Chrysler convertible, a 1953 Jaguar XK120 roadster, a WWII-era Willys Jeep, a Dodge-ish utility truck, a tow truck, a tractor, a larger scale motorcycle, a helicopter, and a couple of airplanes were all part of the Fix All series. The cars’ boxes boasted features like “Over 50 parts” and “For a real mechanic!” As an example, the tow truck came with cast metal box and open wrenches, an adjustable end wrench, a two-piece jack, gas can, hammer, screwdriver, and fire extinguisher. The Jeep came with a star wrench, a screw jack and working lights.

Since the 1950s, Marx had factories in different locations. Among these was a factory in Swansea, Wales, which made a variety of toys for the British market. Example of some of the plastic cars made there were Motorway Station Wagons (which looked like late 1950s U.S. Fords), a remote control 1950 Pontiac, and a Ford Zephyr wagon police car. The Marx factory was in the same industrial estate as the Corgi Toys factory.

The Marx Hudson 13″ toy

In 1948, the Hudson Motor Car Company made a detailed in-house promotional model of its “step down” 4-door Commodore for exclusive use by their dealers. The model was exceptionally well done, and came in four authentic two-tone color combos, but sadly, was never available on the retail market. Some sources erroneously insist this model was made by Marx, but in fact, it was Hudson’s own production effort, manufactured, produced and assembled in Hudson’s main factory.

Soon after, Marx fabricated an injection mold of Hudson’s more precise model and marketed this simplified version as a more inexpensive mechanized toy. It was available as a police car in grass green or a fire chief car in bright red. The clear windows of the original were replaced with a single, stamped metal piece with lithographed images of cartoonish policemen or firemen. The police version even had a shotgun protruding through the windshield. With batteries an oversize roof light lit up and the gun made a corny rat-a-tat sound.

Not one of Marx’s more successful toys, their Hudson was large and unwieldy, being aimed at pre-teens. After newer, more modern American cars appeared, the Marx Hudson quickly became obsolete, resulting in an oversupply on retail toy shelves. By the mid-1960s they were still easy to find across America and one could usually be bought for about a dollar – a nice discount from the original $4.95 list price.

A well-preserved Marx police or fire chief Hudson with original box will still bring from $50 to $100 in today’s market, depending on condition. An authentic Hudson promotional still brings around $2,000. Over the years, professional Hudson experts have upgraded Marx versions to look somewhat like the original promotional – these usually bring from $600 to $800.

Marx also made Studebaker and Packard vehicles especially through the 1930s and 1940s. They often appeared with the Studebaker badge logo in a very promotional way, though evidence of Marx as a promotional provider is uncertain. One of Marx’s later Studebakers was an Avanti with a dented fender that could be replaced with a ‘repaired’ one, which was odd, as the real Avanti had a fiberglass body – and would not dent. A 1948 Packard Fire Chief’s car was one that looked, in theme, much like the step-down Hudson.

Into the 1960s and 1970s, Marx still made some cars, though increasingly these were made in Japan and Hong Kong. Especially impressive were two-foot long “Big Bruiser” tow trucks with Ford C-Series cabs and “Big Job” dump trucks, a T-bucket hot rod of the same large size and some foreign cars like a Jaguar SS100, which was later reissued. Marx made some 1/25 scale slot cars, like a Jaguar XKE remote control convertible. Into the 1970s, Marx jumped on several bandwagons, for example, plastic pull string funny cars of typical 1:25 scale model size, but this was not quick enough to save the company.

Marx sometimes joined with European toy makers, putting their name on traditional European toys. For example, about 1968, Solido and Marx made a deal to sell these French metal die cast models in the U.S. with the Marx name added to the box. The boxes were, for the most part, regular red Solido boxes with the Marx “x-in-o” logo and “by Marx” directly below the Solido script. Nowhere on the cars did the Marx name appear.

The small scale market

During the 1960s Marx offered its Elegant Models, a collection of Matchbox-like 1930s to 1950s style race cars in red and yellow boxes. Also offered were airplanes, trucks, and, in the same series, metal animals boxed in a similar style. Some of the vehicles from this era were marketed under the Linemar or Collectoy names.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Marx tried to compete not only with Matchbox, but with Mattel Hot Wheels, making small cars with thin axle, low-friction wheels. These were marketed, not too successfully, under a few different names. One of the most common was “Mini Marx Blazers” with “Super Speed Wheels”. The cars were made in a slightly smaller scale than Hot Wheels, often 1:66 to about 1:70. Proportions of these cars were simple, but accurate, though details were somewhat lacking.[31] Some cars, however, included such niceties as a driver behind the wheel. While some of the earlier toys had a simpler Tootsietoy style single casting, newer cars were colored in bright chrome paints with decals and fast axle wheels. Tires were plain black with thin whitewalls.